It sounds surreal to even say it out loud, but I’ve been living in America for the majority of my life, ever since I was a teenager. And for 18 of those years, I was legally a transient – hopping from one temporary visa to another. I’ve explored so many nooks and crannies of the immigration system and its myriad provisions, that I’ve become the go-to guy among my friends for immigration questions. Here’s my story.

Disclaimer: This essay is intended to be descriptive of my personal experiences and memories as an immigrant. I am not a lawyer. This essay will surely contain statements that are simplifications, incomplete, inaccurate, or outdated in some way. If you’re an immigrant seeking legal advice, do your own due diligence or talk to a lawyer.

2004 – Student Visa Applicant

I had just graduated from high school in Singapore, and was admitted into University of Michigan for a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering. This was when I first encountered the American immigration system. Using my university acceptance letter, I applied for a F-1 visa – a student visa that would allow me to live and study (but not work) in America for a period of 4 years, for the purposes of getting a University education.

Note: I’m using the above wording very loosely. The visa itself is only required to enter the country. Once you’ve entered the country, there is a different process for remaining “in-status”, which is what gives you the legal authorization to actually live and study in the USA. This weird similar-but-separate system can lead to very interesting outcomes. For example, your visa may expire, but you can still be “in status.” This means that you’re legally allowed to live in the country, but you’re not allowed to re-enter if you were to leave. This applies not just to the F-1 student visa but to most other visas as well.

To be honest, I don’t remember most of the process I went through in order to get my F-1 visa. I’m sure I had to mail a bunch of paperwork to the local embassy. But there is one step I remember vividly – the interview. I had to go to the American consulate in Singapore and meet with a consular officer who is tasked with ensuring my acceptable “intentions.” It turns out that there is an odd requirement for getting a F-1 student visa – you are not allowed to have any intentions of applying for a work visa after graduating. If you are even considering doing so, that is immediate grounds for rejection.

In reality, this is a very strange and contradictory requirement. There are other visas such as the J-1 visa, which explicitly prohibit applicants from applying for other visas immediately afterwards. But the F-1 visa has no such restriction. If lawmakers truly wanted all international students to leave the country after graduation, they can simply pass a rule decreeing that F-1 visa holders should be denied any and all subsequent visas. But they have explicitly chosen not to do so. In fact, they have even gone a step further and enacted provisions intended specifically to give international students the means to continue living and working in America.

And with good reason too – international students as a demographic are highly educated, about to enter their prime working years, and have spent many formative years culturally immersing and integrating themselves into American society. If you’re ever going to let anyone immigrate into the country, this is the one of the best demographics to allow in. And indeed, a large number of international students go on to do exactly that – with full legal approval.

But regardless, the law is the law, and the law proclaims that anyone considering the possibility of working in America, at the time of applying for their F-1 student visa, should be immediately denied. I’m not sure how the immigration officers feel about implementing such a subjective and self-contradictory rule. But that is their job and they don’t have a choice in the matter. And this is one of the main purposes of the interview that I had to attend.

It is interesting to note that the F-1 visa isn’t the only visa that rejects applicants who have an “intent to immigrate.” The TN visa, commonly used by Canadian professionals to live in America, also has the same requirement. If a Canadian citizen wants to work in America on a TN visa, and is considering applying for Permanent Residency later on, that alone is grounds for rejection.

Hence why my heart was pounding wildly as I approached the counter for my interview – regardless of what my true intentions were, I knew that the next 4 years of my life rested solely on some stranger’s interpretation of my intentions. It also didn’t help that growing up in Singapore, this was literally the first American that I had ever met – and he looked dead serious for reasons I still wonder about sometimes.

2004 – College Student at Michigan

Luckily, the interview went smoothly, and I was soon granted a 4 year F-1 student visa. A few months later, I hopped on a non-stop 22 hour flight from Singapore to New York. And after a few short stays with relatives in New Jersey and Ohio, I arrived at my home for the next few years – Michigan, Ann Arbor.

In contrast to the imperious immigration system, I found the people to be extremely welcoming and friendly. I remember once having dinner with a number of American friends, and someone asked me what I planned to do after graduating. Thinking back to my interview at the consulate, I replied tentatively that I wasn’t sure, but I’ll probably go back to Asia. Upon which my friend responded “So you’re just going to take our education and then leave? Nah Rajiv, you gotta stay.” It was a very casual and light-hearted comment, but it genuinely warmed my heart to be treated as a welcome guest and not an interloper.

I could write an entire book about my cultural experiences, but for the purposes of this essay, I’ll remain focused on the immigration system itself. Given that my student visa was valid for a period of 4 years, I didn’t have to deal with the immigration system again for quite a while. But I did need to constantly get new paperwork signed and stamped by my University’s international-student department. It took me a while to realize this, but apparently my F-1 visa was not sufficient in order to re-enter the country. I also needed to get some paperwork stamped by the University immediately before each trip.

This came to a head when I went on a weekend road trip with some friends to Canada. I only found out from my friends, during the drive back, that I didn’t have the necessary paperwork to be allowed back into the country. Funny enough, one of the guys on our trip also had a similar problem – he was a US citizen who didn’t know that he needed to bring his passport, and only had his driver’s license with him. We spent the car ride nervously joking about which one of us will be detained at the border. Luckily for us, the guards at the border waved both of us through without any questions.

It really underscored for me how much of the immigration system’s enforcement comes down to the whims of the officer you happen to be talking to. Fortunately I’ve had mostly positive experiences over the past 18 years, but it’s still unsettling to be at the mercy of any one individual.

The most mortifying but also funniest example of this, was a decade later when my friend’s brother decided to visit New York together with us. He was a Canadian citizen who was born in the Middle East, and had never visited America despite living just an hour from the border. He was also a 6’2 big imposing guy, a devout Catholic, and told the immigration officer that he was visiting New York to participate in an upcoming major Catholic festival. This set off a number of alarm bells and I could hear the rising anxiety in the officer’s voice. He ended up being interrogated for nearly half an hour, during which time he was asked to unlock his smartphone and show the officer his online-dating profile and the messages he had sent to girls through that app.

To this day, my biggest nightmare is having to unlock my phone and hand it over to someone at the border. I keep my deepest thoughts and journals in my online drive, and I would rather risk deportation than share that with any stranger. This is a choice that I pray I will never have to make.

One further complication with the student visa arose towards the end of my sophomore year. As mentioned earlier, the F-1 student visa only allows the recipient to study and live in America, not to work. However, summer internships are extremely common and almost mandatory if you want to land a good job after graduation. Companies are very wary of hiring someone with zero work experience, and internships are used as a signal that someone won’t be completely clueless at the workplace.

Fortunately, the student-visa laws recognize this, and allow students to work temporarily via a Curricular Practical Training (CPT) program. Through this program, students are granted work authorization for temporary employment opportunities that are “an integral part of the school’s established curriculum.” I was fortunate enough to be able to use this program to intern at companies such as Texas Instruments and Intel.

Though there certainly were restrictions. I once interned at a company during the summer, and they wanted to have me work for them part-time during the school year. I wanted to do it as well, but I soon realized that the CPT program informally has a combined 12-month limit across all 4 years of your undergraduate program. (Technically there is no limit at all, but there are significant legal downsides to exceeding this 12-month limit) Hence, I regrettably had to turn down this opportunity. Interestingly enough, I was allowed to “work” as a Residential Advisor at the University dorms, in exchange for free housing and meals. And this didn’t seem to require a CPT at all. Looking back, I’m still unsure how and why the law distinguishes between these two different “jobs.”

2007 – Graduate Student at Stanford

My student visa was initially granted for a period of 4 years, but I completed my undergraduate degree in 3 years. As a next step, I decided to pursue a 1.5 year Master’s degree. This was partly for career development – as an electrical engineer, I knew that my career prospects would be better with a Master’s degree rather than just a Bachelor’s. Especially if that Master’s degree is from Stanford, which I was very happy to get admitted into!

But a significant part of my decision was also driven by the American immigration system. As someone with an “advanced degree”, the immigration system would grant preferential treatment when applying for a work visa or a green card. There are actually numerous companies that require advanced degrees from their immigrant job applicants for this reason alone.

Given that I still had a year remaining in my F-1 student visa, I decided not to apply for a new student visa. I was able to pack up, move to California, and enroll in Stanford as a Master’s student, all while using the same visa I had previously received. There was only one slight complication. My student visa expired in May 2008, but I would only be graduating in December 2008. During these intervening months, because I was enrolled as a full-time student in a legitimate program, I was still legally allowed to live and study in America. However, because my visa had expired, I would no longer be allowed to re-enter the country if I left.

I now found myself in a very precarious situation where I was both legally allowed to be in America, but also prohibited from entering the country. I would often joke to my friends that if I ever fell asleep in their car and they drove me across the border to Mexico, my life would be completely ruined – I wouldn’t be allowed to re-enter America and complete the rest of my degree. In a sane world, there would only be a single set of requirements for living here as an immigrant, and anyone who met those requirements would be allowed entry. But that is clearly not how the immigration system works.

To be fair though, I always had the option of leaving the country temporarily and applying for a F-1 visa renewal. And once I had received the renewed visa, I would be allowed to travel internationally once again. However, if my visa renewal was denied for any reason, I wouldn’t be able to graduate and receive my Master’s degree – a risk that I was not willing to take. Hence why I decided to just sit tight for 6 months and complete my studies on an “expired visa.”

2009 – Full-time job at Intel

In January 2009, I graduated and had a dream job lined up at Intel. It was in exactly the field I wanted to work in (computer architecture) and in a company I’ve idolized ever since my teenage years.

Day to day reality turned out to be far more mundane, but that’s a story for another day.

Now that I was no longer a student, I could no longer use the F1 visa to live and work in America. The next step in my immigration journey would be to apply for the infamous H1B work visa. However, this visa is only granted in October of each year. And it was only January when I graduated.

Thankfully I didn’t need to sit on my butt and twiddle my thumbs for the next 10 months. The immigration system provides a solution explicitly designed to ease this transition from the F1 to H1B visa. International students are automatically eligible for “Optional Practical Training” (OPT) – a program that grants them unrestricted employment authorization for a period of 12 months. As a “better” alternative to the CPT, students are allowed to use this program in the middle of their studies as well, in order to pursue internships. But most people use their 12 months immediately after graduating, in order to bridge the gap in between their graduation and their H1B work visa. And that’s exactly what I did as well.

Which is not to say that getting a H1B visa is easy. It certainly isn’t. Not least of which because of the lottery involved. That’s right, there is a literal lottery involved in getting this visa. Each year, across all of America, there’s a maximum of 85,000 new H1B visas that will be awarded – 20,000 of which are reserved for those with advanced degrees from an American university. If there are more qualified applicants than this limit, a lottery is used to randomly decide who gets the visa and who doesn’t – incentivizing companies to stuff the lottery with as many applicants as possible, in order to maximize the company’s odds. At one of my internships, we used to host “The Deported” parties every year in order to bid farewell to colleagues who got unlucky in the lottery and had to leave the country. For a society that espouses meritocracy, this lottery sure is a strange way of making life-changing decisions.

Historically, your odds in the lottery were still pretty good. But ever since the late 2000s, things have been steadily getting worse. In 2007 when many of my friends graduated from college and applied for H1B visas, their odds were around 60%. And if they had a Master’s or PhD, their odds improved to 80%. This was considered to be a big problem back then – big enough that the immigration system was tweaked to extend the OPT duration from 1 year to 2.5 years, for those who had a job in a STEM field.

As a side note, it truly is fascinating how the immigration system in America is simultaneously both hostile towards and protective of immigrants. This lottery is a self-inflicted problem that could be easily solved by either raising the cap, imposing more stringent requirements, or granting priority to the most qualified applicants. Unfortunately, immigration is a hot-button issue that Congress is afraid to touch with a ten-foot pole. Hence why in the absence of congressional leadership, other stop-gap solutions like the OPT extension are used to keep the wheels from falling off.

At the time when the OPT extension was announced, people figured that this 2.5 year period would allow international students to try their luck with the lottery 3 times. And surely after 3 attempts the chips would fall in their favor at least once. Over time though, the odds dropped so significantly that even the 3 attempts weren’t sufficient for a lot of people. In the most recent lottery, each qualified applicant only had a ~23% chance of receiving a work visa. As is the nature of any lottery, some of the best candidates miss out, while others far less impressive walk away as winners. I personally had a Canadian manager at Google who applied for the lottery 3 years in a row, and failed to get a work visa in all 3 attempts.

My manager was still able to work in America using the TN visa – available only to Canadians and Mexicans – but this makes it significantly harder to apply for a green card.

“Luckily” for me, I graduated in the middle of the most severe recession in recent history – the Global Financial Crisis. As a consequence, there were unusually few H1B visa applications in 2009 – anyone who qualified didn’t have to worry about the lottery. And thus, after 5 years as a student, I was now officially a H1B “Nonimmigrant worker.”

Of all the visas offered in America, the H1B is by far the least popular and most controversial. H1B workers hate it because of all the associated risks and restrictions. Companies hate it because of all the costs, delays, and uncertainties. Immigration hardliners hate it because it “takes jobs away from American workers.” Bigots hate it because a lot of visas go to people of color. Xenophobes hate it because it gives immigrants a pathway to Permanent Residency. And even some progressives hate it because it is “elitist”, disqualifies low-skill workers, or is a “handout to big corporations.”

It’s hard to find anyone who is actually happy with the program. But everyone wants to change it in a completely different way. And that is exactly why it has remained mostly unchanged for the last 30 years.

Interestingly, even though people have such strong opinions on the H1B visa, few people actually understand its most important details. Here are some of the main features of the program, at least from my memory and experience:

- To qualify for a H1B visa, you need to have a job that requires “theoretical and practical application of a body of highly specialized knowledge” and “attainment of a bachelor’s or higher degree in the specific specialty” or “is so specialized and complex that the knowledge required to perform the duties is usually associated with the attainment of a bachelor’s or higher degree.” Hence why most farm workers (or workers in other comparable professions) don’t qualify for the H1B, and need to apply for the H2A or H2B visas instead

- In order to maintain your H1B status, you need to be paid the “prevailing wage” for your industry, occupation and geographic location. Ie, a lawyer in NYC will need to be paid significantly more than a newspaper reporter in Mississippi, in order to qualify for the visa. The Department of Labor actually compiles very detailed statistics around prevailing wages in order to enforce this law – it ensures that H1B workers can’t significantly undercut the market wages, contrary to popular belief. The median H1B worker in 2019 had a salary of about $100,000 – on par with native born workers in the same profession. And more than double that of the median American worker’s salary of $40,000

- If you ever quit your job, or get laid off, you have 60 days to find a new job with an employer who’s willing to file a new H1B petition for you. If you fail to find a new qualifying job, and don’t qualify for any other visa, you’ll need to leave the country immediately.

This is the single biggest source of legal anxiety that immigrant workers face. Imagine losing your job, and on top of the usual financial concerns, you now also have a 60-day deadline to find a new job. And if you’ve spent the first 45 days interviewing only to wind up with rejection notices, you now have just 15 days to withdraw your kids from school, pack up all your belongings, buy plane tickets and hotel accommodations, and move your family to a new country

- The H1B is for a specific job, at a specific company. You aren’t allowed to have a “side hustle.” (Amusing anecdote: I was once selected to be a sperm donor, only to be forced to pull out – the organization had a policy of paying all their donors a nominal amount, and this would have jeopardized my immigration status). If you ever decide to change your job role or switch companies, you’ll need to file and be approved for a new H1B petition. When people describe H1B workers as indentured servants, this is usually what they are referring to. Though it is hyperbolic, since it is possible to switch jobs – not to mention that H1B workers are free to quit and return to their native country at any time. And to be frank, it is idiotic and patronizing to describe white collar professionals earning six figures in modern America as indentured servants

- Despite the above perception, the H1B visa does have provisions to help with job mobility. Once you’ve been granted a H1B visa, you don’t need to go through the lottery again. Your new employer can file a H1B petition on your behalf, which would then allow you to switch employers. In fact, you don’t even need to wait for the H1B application to be approved – you can start working for your new employer as soon as they have mailed the application. Or if you prefer to wait for the approval, your employer has the option of paying $2500 to guarantee a response within 2 weeks

- When you get approved for a H1B, it only lasts for 3 years. You then need to keep renewing it every 3 years, using the same process and requirements as your initial application (except that you get to skip the lottery). If you fail to renew your H1B, you’ll need to leave the country immediately

- If you haven’t made progress towards getting a green card, you can only work on a H1B visa for 6 years. After which you’ll need to leave the country

- Even though you’re a “nonimmigrant,” you still need to pay taxes for social security and medicare. You also file taxes every year with the IRS as a Resident, subject to the same taxes and brackets as all citizens, since you’ve spent most of the year living in America

All in all, the H1B program is something no one likes. But it serves its role adequately as a stepping stone towards something far more stable – Permanent Residency. Which was the next stop in my journey.

2010 – First-Time Green Card Applicant

With my H1B visa acquired, the next logical step would be to apply for permanent residency. As an “Employment-Based” applicant, there are 3 main pathways through which workers can apply for Permanent Residency: EB1, EB2 and EB3.

The EB1 pathway, the “best” route to a Green Card, requires you to have “extraordinary ability” as demonstrated through prior career accomplishments (ie, graduating from Harvard with a perfect GPA doesn’t cut it), or be an “outstanding professor and researcher”, or work as a manager in multiple countries in a Multinational corporation.

Given that managers are a dime a dozen in any country, it seems odd to put managers in the same category as people of “extraordinary ability,” but I digress.

Most notably for EB1 applicants claiming to be outstanding professors or to possess extraordinary ability, they don’t actually need to have a job offer in America – they can file a petition for themselves, while living anywhere in the world, and working at any job. This gives them a lot more control and freedom in their immigration journey, compared to other applicants.

The next pathway is the EB2, which requires you to have either an “advanced degree” or “exceptional ability.” Most people utilizing this pathway claim the “advanced degree” criteria, which is relatively straight-forward to meet. You need to have a postgraduate degree, such as a Master’s, from an American accredited university – or you need to have a Bachelor’s degree, along with 5 years of work experience in a career related to your degree.

This pathway is also notably different from EB1 in that it usually requires you to have a job offer in America, and your employer is the one who files the petition on your behalf. And losing your job or leaving your employer would often require you to restart the entire petition. As you can imagine, this can put you at the mercy of your employer over a period of multiple years, and can create an unhealthy power imbalance.

The last, EB3, is very similar to EB2 – except that the “advanced degree” requirement is waived. Petitioners must either be “skilled workers”, “professionals” or “unskilled workers for which qualified workers are not available in America.”

As is standard for almost all recent college graduates with a Master’s degree, Intel petitioned for me under the EB2 category. In fact, this is something that Intel could have done immediately after I had accepted their job offer. Filing the petition only requires you to have a job offer waiting for you in the future – it doesn’t require you to actually be working for that employer.

If I had known better, I would have even insisted on this when negotiating the job offer – because of a quirk in the annual quotas, I could have received my green card far earlier if only Intel had filed my petition immediately. Unfortunately, Intel’s policy was to wait until I’ve received my H1B visa, and also to wait for the economy to recover from the recession. Hence, it wasn’t until late 2010 when Intel finally got around to it. A decision that would have major repercussions for the next decade.

The Application Process

The first step in the application process is known as Permanent Labor Certification (ie, PERM). As part of this certification, your lawyers need to put together a list of specialized skills needed to do your job, and then provide tangible evidence demonstrating that you possess those skills.

Interestingly, the certification also requires your employer to advertise the job opening in some form, such as newspaper ads or job boards. And attest that they weren’t able to find any “qualified, available and interested” American citizen to fill that job opening. If they find even a single person who is “qualified, available and interested”, the certification process is immediately terminated and needs to be restarted again some time later. For the first time in history, employers are incentivized to post the least effective job advertisement possible. I have no insight into the specifics around how any company conducts these job advertisements, but incentivizing failure is hardly a recipe for success.

On the surface, both of the above requirements seem reasonable. After all, given the limited quota of immigrant visas, wouldn’t we want to prioritize those with specialized skills that would most benefit the economy. And wouldn’t we want some way to demonstrate that those skills are actually hard to find, and that the applicant possesses those skills.

Unfortunately, there are severe restrictions around what qualifies as a “skill” and what doesn’t. And the PERM definition is significantly out-of-touch with the reality of modern workplace needs.

For instance, if you talk to leading experts on how to build a great team of software engineers, they would tell you to avoid hiring candidates based on their pre-existing knowledge of specific tools and frameworks. For example, they would recommend hiring a good AngularJS developer, over a mediocre React developer, even if your specific project uses React. The reason is that these highly specific tools can be learnt by good software engineers. Instead, the advice is to hire smart, talented, hard-working and motivated software developers, even if they don’t have experience with the exact tools you’re using.

In the PERM certification however, “smart, talented, hard-working and motivated” are all meaningless terms that can’t be used to justify hiring someone. If someone graduated from a leading university such as MIT, that is irrelevant in the labor certification process. If someone got straight-As in University, as opposed to scraping by with Cs, that is irrelevant. If someone has excellent references from their professors or past managers, that is irrelevant. If someone has demonstrated through the interview process tremendous intelligence, problem-solving skills, and an ability to navigate workplace challenges, that is irrelevant.

What is highly relevant in the labor certification process however, are exactly the things that experts tell you to ignore when making hiring decisions. A university class taken on the subject of relational databases. Two years of work experience with the React framework. Two years of experience with object oriented programming. These are the things that really matter in the labor certification process. These are the things that determine whether someone is “qualified” or “not qualified.” And hence, these are the things that companies need to build their entire PERM application around.

In my view, this exercise is both flawed and prone to abuse. Instead of having government bureaucrats judge the qualifications of someone in a completely different profession, the immigration system would be better served by market-based mechanisms and signals. For example, if the average American worker earns $40,000 a year, the average software engineer earns $125,000 a year, and a company has decided to pay someone $150,000 a year, it’s hardly a stretch to believe that the applicant is a talented professional. Especially in comparison to another applicant in the same profession and city who’s getting paid below the median wage.

This also gives companies a way to put their money where their mouth is. Are you claiming that your employee possesses advanced skills that are valuable and hard to find locally? If so, surely that should be reflected in their paycheck. Such market-based mechanisms and signals would be far more robust, compared to bureaucratic checklists and paperwork.

Approval … and Long Wait

Returning back to my own story – after a lengthy preparation and certification process, Intel eventually completed the PERM certification in late 2011 – an entire year after we first started preparing for it.

The immediate next step after PERM completion is the I-140 petition, which mostly consists of sending in the appropriate paperwork pertaining to your university degree, job details, and the recently completed PERM certification. After a 3 month wait, this too was approved at the very start of 2012.

Normally, getting the approved I-140 is a major milestone, and means you’re close to receiving your Green Card. Unfortunately for me, my journey was only just beginning.

According to US law, “national origin” is a protected class, similar to race and gender. It is illegal to discriminate against someone on the basis of their national origin. Interestingly enough, American immigration law does exactly this. How long you need to wait for a green card depends explicitly on which country you’re born in.

For anyone interested in the details, immigration law enforces a per-country quota for the number of Green Cards that can be issued each year. Even worse, this quota does not account for population differences at all. India, with a population of 1.4 billion, gets the exact same quota as neighboring Sri Lanka, which has only 20 million people. Mexico, with a population of 130 million, get the exact same quota as neighboring Belize which has only 0.4 million people. Hence why applicants from India and Mexico face far longer wait-times compared to Sri Lankans and Belizeans.

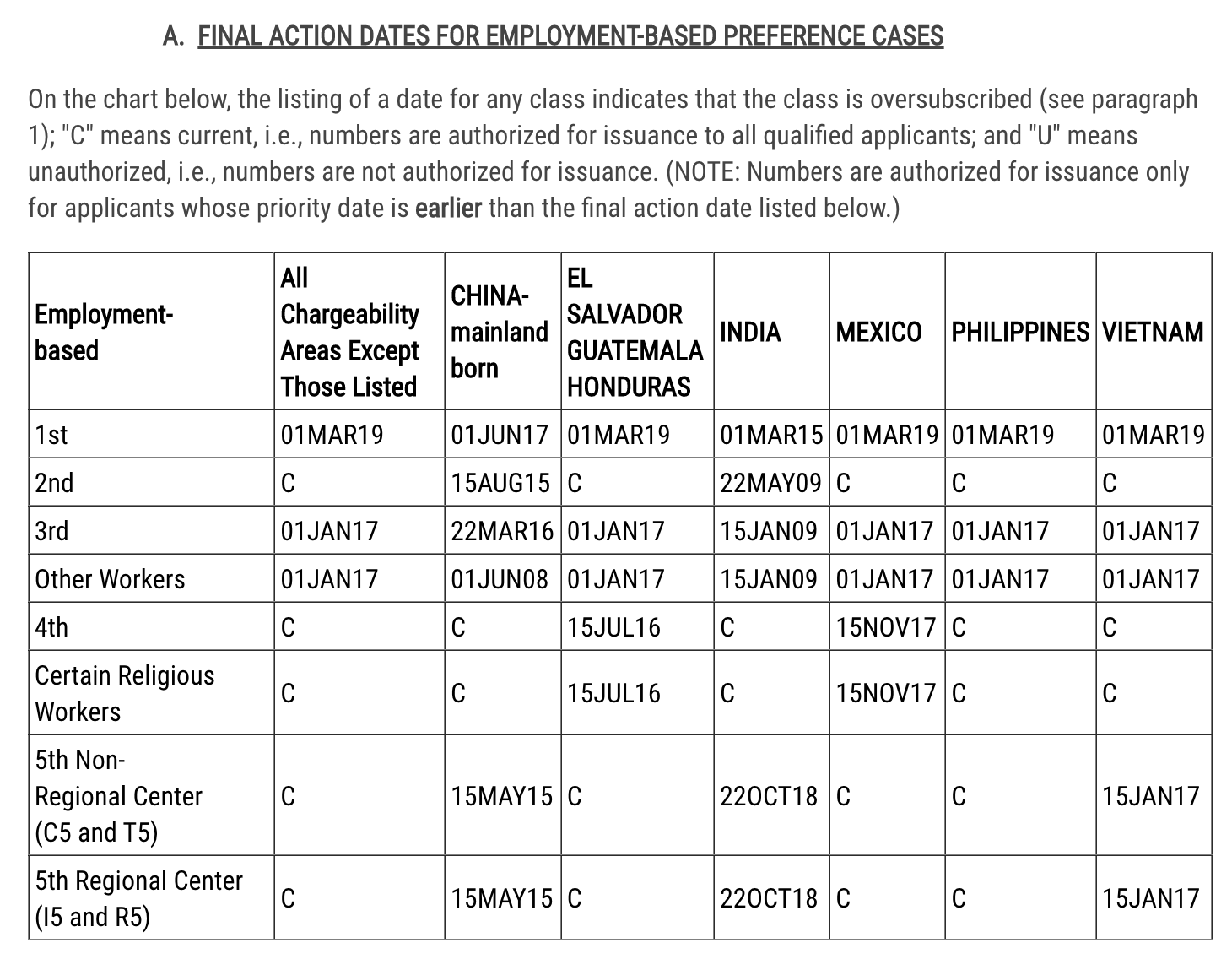

The above image from March 2020 shows the wait time for green card applicants based explicitly on the country they were born in. If you were an extraordinarily talented applicant (1st employment-based category) born in India, you’d have to wait for 5 years (from March 2015 – 2020). Whereas if you were a less qualified applicant (2nd Employment-based category) born in neighboring Pakistan, you don’t need to wait at all.

Specifically in my case, I fell into the 2nd Employment-Based category. If I had been born in any country besides China or India, I would not need to wait at all – I could have received my Green Card within the next year. But because I was born in India, I needed to wait for 11 additional years.

Interestingly, the 11 year wait is only known in hindsight. The above image shows us that someone who was approved in 2009 would have had to wait until 2020. Whereas the wait time for someone who was approved in 2020 can only be guessed at. It could optimistically be lower. It could also be far higher. Some reports have estimated that if you were born in India and applied in 2018, you’ll have to wait for 58 years to receive your green card. That is not a typo – you would get your green card just in time for the birth of your great-grandchild.

In any case, once the reality of my situation sunk in, I realized that I needed to dig in and prepare myself for the long haul. I wouldn’t be receiving my green card anytime soon, and I would need to continue as a H1B worker for the foreseeable future. I might as well accept it, and try to make the most of the situation.

2012 – New Job at Sun Microsystems

In the tech industry, people in my situation are a dime a dozen. It is commonplace to meet immigrants from China and India who have an approved I-140 petition, and are now stuck in immigration limbo. In addition to the H1B portability issues mentioned earlier, immigration law is a mixed bag in terms of job portability for such workers.

On the one hand, if they decide to switch companies, these workers would have to restart their application process all over again, starting with a fresh PERM (which always faces the risk of rejection). But on the other hand, even if you do need to apply all over again, you still get to “keep your place in line.” Ie, even if I’m facing a 11 year wait, I won’t have the timer reset every time I switch jobs.

(Interesting story about that. “Keeping your place in line” is referred to as Priority Date retention. The rules and regulations around this have changed many times over the past decade. Back in 2012, I asked multiple different lawyers about whether I’ll get to retain my priority date, and got multiple different answers. Some were highly confident that I can retain my priority date, while others were equally confident that I wouldn’t be able to do so. Apparently this has long been a gray area, and different people have experienced different outcomes. Luckily for me, right when I was in the middle of this dilemma, USCIS released an official statement announcing that people like me would be allowed to retain our priority dates. If not for that timely announcement, my career would have played out completely differently.)

Note that the regulations have changed again since 2012, so make sure to do your own due diligence before making any life decisions. Once again, this essay is intended for storytelling purposes, not for legal advice.

Because of the risk involved in filing for PERM all over again, many immigrant workers prefer to stay at the same company and wait it out until they receive their Green Card. Contributing to the common perception of them being “indentured workers.” And accusations that employers prefer to hire immigrants because they are “indentured” and less likely to leave.

In my experience, companies overwhelmingly have an aversion to hiring immigrants, because of the costs, delays, and uncertainties involved. Half the companies at my undergrad career fair flat out refused to interview anyone who required immigration sponsorship. But immigration hardliners still love to peddle the “exceptional native-born worker loses his job to a less qualified immigrant” trope.

I personally felt differently. I wanted to be able to grow my career by pursuing the best job opportunities, and I was willing to take some risks to do so. Hence why in 2012, when I started getting cold-emails from almost every major Hardware company in Silicon Valley, I took them up on their offer and started interviewing elsewhere. Over the next 3 months, I landed almost half a dozen job offers at companies such as Nvidia, Qualcomm and Broadcom. And eventually ended up accepting a job offer (and promotion) from Sun Microsystems (shortly after it was acquired by Oracle).

The H1B “transfer” went smoothly. Sun filed for a new petition once I accepted their job offer, and paid to have it processed within 2 weeks. And once I received the approval, along with a 3-year extension, I gave my 2 weeks notice and left Intel. I was now “in status” to work for Sun until 2015.

As expected, I then had to go through the PERM and I-140 application process all over again. I knew I still had a 10 year wait ahead of me, so I figured this wouldn’t have any material impact. I also figured that I now had 2 additional years of work experience, a more senior title, and a higher salary compared to the last time I had applied – so the process would be smoother.

Turns out, it wasn’t. In Aug 2013, a year after I first joined, Oracle filed for my PERM. And 7 months later, in March 2014, the PERM was selected for an audit. By the time I got to Dec 2014, the PERM was still stuck in audit. I’m not sure what the issue was, but at least it didn’t seem to have any material impact, since I was stuck in limbo anyway for the foreseeable future.

2015 – New Career as a Software Engineer

By the time I got to the end of 2014, I came to the realization that the Computer Hardware industry wasn’t where I wanted to spend the rest of my career. Back in University, I loved the topic of Computer Architecture. It was filled with fascinating brainteasers, and really cool challenges that I loved solving. But after 6 years of working in industry, I realized that the day-to-day reality was far more monotonous and slow-paced. And that the software industry, home to the 4 largest companies in America, is the most exciting and lucrative place to be. Hence why I made the difficult decision of transitioning my career from a Hardware Engineer to a Software Engineer.

I didn’t realize this at the time, but the immigration system was a big hurdle that I should have paid more attention to. As discussed in the previous section, in order to successfully get PERM certification, you need to demonstrate tangible skills and qualifications – such as specific university courses or prior work experience that is very similar to your present job requirements. For someone who has a Computer Science degree and prior jobs as a Software Engineer, this is easy to do. But for someone graduating with a different degree, this is much harder to do.

This is particularly relevant to the Software industry, because it is very commonplace to meet elite programmers who graduated with completely different degrees. Some of the best programmers I’ve worked with are “self-taught”, and have degrees in other subjects such as Mathematics, Physics, Mechanical Engineering, etc. Because there’s such high demand for talented developers, and because companies are confident in their ability to identify talented developers from “non-traditional backgrounds”, it is not unusual to see such developers go on to build very successful careers at elite companies such as Google and Facebook.

As far as the immigration system is concerned however, they would still have a hard time demonstrating that they are qualified for a EB2 or EB3 petition, and deserving of a green card. And in some cases, they may even find themselves deported if they are working in a different field using an OPT.

Luckily for me, my degree was in a very similar field (Electrical Engineering), with a focus on computers, and my day-to-day responsibilities had always revolved around coding. After a month of interviewing, I landed a job offer at a Hedge Fund (Engineers Gate) all the way across the country. Shortly after I enthusiastically accepted, my new employer filed a H1B petition, which was approved without any problems. I then moved from California to New York and started work as a Software Engineer.

Over the next year, my new company went through the PERM certification process once again, for the 3rd time in 5 years. Surprisingly, it went even smoother this time, despite my career change. It took a while but by mid-2016, I had once again received an approved I-140 – my second approval in the past five years. They also succeeded in retaining my “priority date” from my initial approval at Intel. Ie, I didn’t have to wait 11 years all over again – I only needed to wait a “mere” 5 years more. I breathed a big sigh of relief, though funny enough, it turned out not to matter at all.

One last thing to mention during my days at Engineers Gate. Shortly after I began working as a Software Engineer, I caught the entrepreneurship bug. Unlike most other professions, software engineering lends itself very easily to entrepreneurship. Any talented software engineer with an idea, and a budget of $100, can spend their evenings and weekends bringing their idea to life. This minimal barrier to entry is exactly the reason we have seen a cambrian explosion of software startups in the past few decades. And the proverbial technology startup founded by a bunch of college students in someone’s garage. And as soon as I got my feet wet, I was hooked as well.

There was just one problem. Immigration law is surprisingly ambiguous and unwelcoming towards H1B workers wanting to build their own startup on the side. As mentioned earlier, H1B workers are only allowed to work for their sponsoring employer, and aren’t allowed to have a “side hustle.” Any secondary source of income, even if it’s from a business that you’ve built from the ground up, would violate the terms of your H1B visa. And even if you aren’t drawing any income, simply running a startup in an “active” manner, puts you at risk of getting deported.

Which is very unfortunate, not just for the worker herself, but also for the wider economy. When debating the merits of immigrant workers, the most frequent argument in their favor is that many go on to become job creators – thus benefiting American workers. An astounding 55% of America’s billion dollar startups had at least one immigrant founder. Given this context, and the extolling of immigrant job creators, it is puzzling that immigration law actively discourages and punishes H1B workers who want to spend their evenings and weekends building a business.

For this reason, I never incorporated my business idea, didn’t seek out investors, and made sure to never draw any income from it. I did build it, had a ton of fun doing it, and learnt a tremendous amount in the process. But it remained as a hobby and a passion project – it never took the next step into a legitimate business venture.

2016 – My Days At Google

After some time at Engineers Gate, I was seduced into leaving by the promise of a promotion and a substantial pay increase. I feel a bit guilty even today for leaving shortly before my 2-year anniversary. But it was hard to say no to Google, the mecca for software developers worldwide!

There was only one roadblock. My H1B work visa. As mentioned earlier, the H1B work visa can only be held for a maximum of 6 years. Except that if you’re born in India, it will take you more than 10 years to get your Green Card. Clearly something doesn’t add up – it would be exceedingly cruel to make someone wait 10 years to get a Green Card, only to deport them halfway through because they don’t yet have a Green Card, and then reject their Green Card petition because they have been deported and are no longer working for that employer.

Thankfully, the immigration system offers a solution to this problem. If you have an approved I-140 petition, you are exempted from this 6 year limit, and are allowed to keep extending your H1B visa in 3-year increments.

Normally this would have solved my problem immediately, because I already had an approved I-140 petition way back in 2011 at Intel. Unfortunately, Intel had a policy of “withdrawing” their I-140 petition if the employee decides to leave the company. This was the same employee-hostile policy that caused me tremendous headaches back in 2012, and one that set Intel apart from other silicon valley companies with far more employee-friendly policies.

There does appear to be some legal gray area, around whether H1Bs can be extended past 6 years using an approved I-140 petition that was later withdrawn by the company. Some sources suggest that it is indeed possible, and the rules have changed even more in recent years as well. Regardless, after talking to Google’s immigration lawyers, they recommended that I sit tight and wait for a new I-140 approval before making the switch. Luckily I was only about a month away from my I-140 approval, but that certainly was a very angsty month!

Finally, in September 2016, I was able to get yet another approved H1B petition, and started my new job at Google. There isn’t too much else to say about my time at Google that is noteworthy from an immigration perspective. I went through the PERM certification process once again, got through it without any problems, and found myself at the start of 2018 with yet another I-140 approval. My 3rd in 7 years. I was getting closer to the finish line, but still had another 4 years to go.

2019 – Amazon – My Last Corporate Job

I could write an entire essay about my experiences at Google, but suffice it to say that it didn’t live up to the rose-colored glasses I came in with. Hence why I was open to considering other opportunities after a few years, when Amazon came along offering a significant pay increase.

After learning from my past experience at Google, I resolved to start at Amazon as soon as possible after the job offer was made. But there was one roadblock – under the Trump administration, which was a lot more hostile towards immigrants and H1B workers, premium processing was no longer available for H1B petitions. As a result, I faced a very lengthy wait before receiving my H1B approval from Amazon. Hence why I decided to take more drastic measures.

By immigration law, if you’re already working on a H1B and are looking to change jobs, you actually don’t need to wait for the new H1B petition to be approved. You’re technically allowed to start working for your new employer as soon as the new H1B petition is sent. By this time, I had gone through the H1B petition process 5 different times, with 4 different companies. And all of them were free of complications. Hence why I was more optimistic this time around, and decided to start working at Amazon even before the H1B petition was approved.

Looking back, this was a dangerous gamble. If my new H1B petition was denied for any reason, I would need to stop working immediately, and I would have been deported if I didn’t find a new job within 60 days. My optimism might also have been misplaced – all my previous petitions were under the Obama administration, and my latest petition was under the Trump administration which adopted a much harsher stance towards H1B applicants. Sure enough, for the first time, my H1B petition was selected for an audit.

When I describe this story to my friends, I like to picture myself as a pawn caught in the crossfire between Trump and Bezos who were publicly feuding at this time. I have no idea why my H1B was selected for an audit this time around, but I’m sure the truth is a lot more mundane. Regardless, I eventually got my H1B approval after about half a year. Though in retrospect, I should have taken this as a warning sign.

A Beach Vacation Gone Wrong

At this point, we’re going to go on a detour and say a few words about the more mundane realities and difficulties of life as a H1B worker. You’ve heard me mention repeatedly that I applied for and received H1B approvals every time I switched companies. These approvals did indeed give me the right to live and work in America. Ie, they granted me “valid status.” However, these approvals do not allow H1B workers to re-enter the country if they leave. For that, you need to have a “H1B visa stamp”. And because these stamps are only valid for 3 years at a time, it is very common for H1B workers to be simultaneously “in status” but also on an expired visa stamp.

Annoyingly, the H1B visa stamping process is completely distinct and different from the H1B application process. The only way to get your H1B visa stamped is to leave the country and physically go to a US embassy outside of America. In order to even enter the US embassy, you need to make an appointment online, and it is not uncommon to face multi-month wait times for an appointment. Once you get to the embassy, interview with a consular officer, and submit all the necessary paperwork, you then need to hand over your passport – which prevents you from traveling anywhere else. It then takes them a week or two to process it and return your passport to you. And you need to repeat this entire process every 3 years.

It still puzzles me why the H1B visa stamping can’t be done concurrently with the H1B application process. Or at the very least, from within America closer to people’s homes.

Most of the time, the above process goes as expected. Prior to 2019, I had gone through this process 4 different times, in Singapore, England and Canada, and had yet to encounter any unexpected problems. But I had heard of horror stories from close friends. One of my friends was selected for further review, for unknown reasons. As a result, even though she had an approved H1B petition, she was unable to re-enter America for many months while the review was pending. Luckily her company was understanding and allowed her to work remotely during this time. But I’m sure there are people out there who have lost their jobs, and hence their immigration status, as a result of such bureaucratic obstacles.

It was in this context that I found myself facing a bleak situation when getting my stamp renewed in the Bahamas. There was a 4-month wait time just to make an appointment, so I had to plan out everything in advance. On the day of the appointment, I made sure to arrive an entire hour before my allotted time. Once it was my turn to enter the embassy, I was suddenly told that I couldn’t enter because I had my laptop and smartphone with me – I had brought them along to ensure that I didn’t get lost, and in case the consular officer wanted to see any other evidence not mentioned in their checklist.

I asked them where I could keep my laptop and smartphone – they replied that they don’t provide any place where I can keep them. I asked if there were any shops nearby that provided lockers, or would hold on to my belongings – they replied that they cannot provide any such advice and I’d need to figure that out for myself. I asked if I could walk back to my hotel, drop them off, then come back for my appointment – they replied that if I’m not back in time (I wouldn’t, my hotel was far away), they wouldn’t let me in, and I’d need to make a new appointment (which would mean waiting for another 4 months).

At this point I was on the verge of panicking. I seriously contemplated hiding my laptop and phone in a nook somewhere on the street, and praying that no one would find it. Luckily, there was a hotel nearby, and the receptionist was kind enough to hold on to my belongings – he was probably used to fielding such requests from panicked visa applicants.

With that issue resolved, I was able to enter the embassy and take my place in line. But it turned out that my problems were only just starting. The person reviewing my paperwork was extremely unhappy with it. I hadn’t provided sufficient details in response to one or two of the questions. I had never encountered such a problem in my four previous applications, but in her opinion, I had committed a grievous error.

I offered to provide her with the answers right then and there – she said that wasn’t good enough. I told her I’d be happy to go online, fill out a fresh set of paperwork with more detailed answers, and come back to the embassy either later that day or the next day, if she would grant me permission to re-enter the embassy – she replied that she can’t give me any such permission, and I would have to make a new appointment. I tried explaining to her that there’s a 4 month wait for a new appointment, and I won’t even be allowed to return to my job and my home during this time – she got frustrated with me and called security over. I made a last ditch effort to plead my case – she told me to email the embassy with a request for an emergency appointment, and shooed me away.

The following day was a nerve-racking one. I was staying temporarily in a hotel, paying $300 per night, for what was meant to be a 2-week vacation. And I suddenly found myself potentially stranded here for the next 4 months. This was the worst-case scenario I had always heard about, but didn’t think would happen to me.

Luckily, my email request for an emergency appointment was granted, and I was able to return to the embassy again later that week. This time around, things went smoothly, and I even had the pleasure of interviewing with a consular officer who was very pleasant and friendly. I still ended up missing my return flight, and had to extend my vacation by an additional week, but I was soon able to return home once again.

2020 – A Big Change

Back to the main story. With my H1B successfully received, the next step was to file yet another PERM. After going through the exact same process all over again, and waiting a year, I found myself in 2020 with yet another approved PERM labor certification. For the 4th time in 10 years, the Department of Labor certified that I was sufficiently qualified to be a Permanent Resident.

Now normally, this is the step where I would find myself stuck in limbo again, waiting with all my fellow Indians in the back of the metaphorical bus. Except this time, things were different. This time, I was married.

We’ve all heard of green card marriages, where an immigrant marries a citizen in order to get a green card. But surely it wouldn’t help me in any way to marry someone who is on a temporary work visa, right?

Wrong. Remember what we discussed earlier about how your wait-time depends on your country of birth? Turns out there is one exception to this. If you marry someone who was born in a different country, you get to use that country as your origin as well. In essence, someone born in India can skip the ridiculous 50 year wait by marrying someone who is born in literally any other country besides India. Which is exactly the situation I found myself in, when I fell in love with and married my wife – an Australian citizen who was working in America as a university professor, on a temporary work visa.

Obviously immigration benefits are an awful reason to spend your life with someone, and that is certainly not the reason we got married. But it was a nice unintended perk! I had already been waiting in line for 9 years at this point, and was nearing the end of my wait, so it didn’t really benefit me a tremendous amount. But it did mean that I didn’t have to wait any longer. For the first time, I was eligible to get my green card… as soon as the immigration agency got done processing our last and final petition – the I-485 petition for “Adjustment of Status.”

Historically, once you had an approved PERM and filed your I-485, you would get your green card within 6 months – physical interviews were waived for most “low risk” employment-based applicants since the submitted paperwork already contained all the relevant information. But that all changed when the new Trump administration mandated that everyone needs to be interviewed in person, without any corresponding increase in funding or staffing for the immigration agency. Coupled together with the COVID pandemic, we now needed to wait much longer – potentially up to 2 years.

(It also didn’t help that there was a mix-up with the medical examination requirements. In order to approve the I-485 petition, the applicant needs to provide a Medical Examination report signed by a civil surgeon. Ie, a more modern variant of the Ellis Island health checks. As part of the requirements, the Medical Examination report is only valid for 2 years after the date of signature. However, the time taken to process the I-485 petition can itself exceed 2 years. Hence, our immigration lawyers told us not to get the medical examination upfront – usually we would be given an interview date, and told to bring the Medical Examination report along. Except that in our case, after many months of waiting, we received a notice that our petition has been suspended and will not be resumed until we provide the medical report by mail. We likely would have received our approval sooner if we had just provided it upfront.)

There was one silver lining however. Within a few months of filing our I-485 petition, my wife and I both received our Advanced Parole (AP) and Employment Authorization Documents (EAD). For the first time in almost a decade, I no longer needed to rely on my H1B visa in order to live, work and travel. The AP allowed us to travel and re-enter the country at any time (no more US Embassy appointments required), and the EAD allowed us to take on any job we wanted.

The latter was particularly handy for my wife because her temporary work visa was expiring soon, and she no longer needed to worry about renewing it. It was also handy for me with my entrepreneurial ambitions – for the first time in a decade, I was free to pursue any “side-hustle” I wanted, and to start my own company without any restrictions. Both of which I would go on to do over the next year.

2021 – Complications as a Job Creator

It was now mid-2021 – almost a year since we had filed our I-485 petitions, and we were still waiting with no end in sight. If not for COVID delays and recent immigration changes, we would have already received our green cards by now. (And if I wasn’t born in India, I would have received my green card an entire decade earlier.) We were on the very last leg of the immigration marathon, but we had little idea how much longer we would need to keep waiting.

It was around this time that I was contacted by a startup incubator. As a software developer with a strong resume, I was used to getting emails from recruiters for various job openings. Over the past couple years, I tuned out all such emails and had no intention of switching companies again. But this was different. The incubator had identified a compelling market opportunity, as well as investors who were ready to commit significant funding. They were looking for a technical-lead to be a founder and build the startup from the ground up.

At this point, I had spent 12 years working in the corporate world, at companies such as Intel, Google and Amazon. I had learnt a ton from these experiences, and saw first-hand both what worked well and what didn’t. I was no longer content to abide by the entrenched bureaucracy that I saw holding back most large corporations – I was eager to make the leap into executive leadership, and put into practice the numerous ideas I had percolating in my head. Hence why the opportunity to be a startup founder, was too compelling to pass up.

Obviously immigration was a concern for me. If I had more clarity around when exactly our I-485 petition would finally be processed, maybe I would have stuck it out. But with no end in sight, I decided that I wasn’t going to put my life on hold indefinitely. Thankfully, the immigration system had a provision designed to help people in exactly my situation.

Previously every time I switched jobs, I had to start over from square one, with the PERM certification process. This is a significant hurdle that dissuades a large number of immigrants from switching jobs. But there is one slight reprieve. If an applicant has filed an I-485 petition, and it has been pending for over 6 months, they are allowed to switch jobs and stay the course with their existing I-485 petition. The only thing they need to do is fill out a 7-page form attesting that the new job is sufficiently similar to the old one.

As you can imagine however, there is significant subjectivity in determining if two jobs are “sufficiently similar.” To quote the immigration agency, “If you change jobs or receive a promotion, USCIS will determine whether you remain eligible for a Green Card on a case-by-case basis and based upon the totality of the circumstances.” What is similar to one person, may not be similar to another. In theory, getting a promotion or similar career progression should not be a problem. But if you used to be a “Software Developer” and your new job elevates you to a “CTO”, would that be a problem? No one can say for sure.

Historically this provision was rarely used – most I-485 petitions were processed in about 6 months anyway, so very few applicants were still stuck waiting after 6 months. But with recent delays and logjams, this became the norm for most applicants, including me. Hence why this provision has now become an essential pathway for immigrants wanting to pursue compelling career opportunities, and not be handcuffed to their existing employer. And after talking to multiple lawyers and being reassured that I have minimal cause for concern, this is exactly what I decided to do as well.

Over the course of the summer, my co-founder and I made all the necessary preparations to found our new company and close our financing round with a venture capital firm. We both planned to resign from our existing jobs in mid August, and start full-time work at our new company in September. Everything seemed to be going smoothly… until the very last minute.

I had been waiting all this time for an update on my pending I-485 petition. As luck would have it, just one week prior to my planned resignation, I got that update. My immigration interview was scheduled for the end of August, just one day before what would have been my last day at Amazon, and two days before the start of my new job at our startup.

This interview is the very last step in the immigration marathon. Most people get their green card approvals within a week of this interview. Given that my interview was now just a few weeks away, the “safest” thing to do would be to simply stay put at Amazon and collect my green card. But by this point, my co-founder and our investors had all made significant commitments in order to get our startup launched. My dropping out at the very last minute would have torpedoed all their plans, and I didn’t want to let them down after all the commitments we had made to one another.

“So why not just postpone your resignation by 2 weeks until the interview is over?” Because doing so would constitute immigration fraud, and can potentially get you deported even after you’ve received your green card. In order to get my green card, I must “intend” to work “permanently” at that job upon receiving my green card. Switching jobs immediately after receiving a green card can be interpreted to mean that your petition was made in bad faith. This can lead to revocation of your green card and/or denial of naturalization.

This rule is yet another interesting duality in American immigration law. On the one hand, there are provisions designed explicitly to enable job portability, because legislators recognize that job portability is in the best interest of both society and the economy. But simultaneously, there are other provisions that will dissuade you or outright punish you for not wanting to work permanently at a single company. Switching jobs immediately before getting your green card is a short-term hassle – but switching jobs shortly afterwards can get you in severe long-term trouble. And this is exactly why I went ahead and handed in my resignation notice… just 2 weeks prior to my immigration interview.

As we got closer to the interview date, my wife and I started laboriously prepping ourselves. There were an enormous number of documents that our lawyers advised us to bring “just in case”, and we were already nervous that we didn’t have originals for a number of these. I mentally rehearsed the answers that I would give if questioned about my job responsibilities and anything else listed on my PERM. It certainly didn’t help my anxiety that my 1985 Indian birth certificates all had problems of some kind – one of them didn’t have my name listed, and the other had my birth-date wrong.

Because my wife was also getting her green card through my I-485 petition, we also had to be prepared to demonstrate that our marriage was not a sham. I had no idea what my wife’s favorite color was, I personally didn’t even have a favorite color, and we had swapped bed-sides a couple of times in the past few months. But during the interview, we had better be prepared with consistent answers to any such questions!

The day before our interview was spent frantically printing out hundreds of pages of documents… and running around town looking for new ink cartridges when our printer ran dry. On the day of the interview itself though, we both felt happy and excited. Our long journey was almost at an end! We drove over to Newark, made our way to the immigration office, and waited for our turn to be called. Looking around at the other faces in the room, my wife and I seemed to be the only ones in high spirits. Everyone else looked nerve-racked and understandably so – if the interview didn’t go well, that would be the end of their American dream.

After some time, we were called over to the interview room, and met with the friendliest person I could have hoped for. She was cheerful, gregarious, and treated us with kindness and respect. She had reviewed our files beforehand, and told me that she didn’t need to see the vast majority of the documents we had brought. After a brief and friendly chat, she excitedly told us that we were approved and would be receiving our green cards! Words I had been dying to hear for over a decade!

A small part of me just wanted to slink away and end this ordeal immediately. But I knew I had to stick to my earlier decision and be fully transparent. I told her that even though I was still employed at Amazon on that day, the next day would be my last. I handed over the paperwork for my new job, the certificate of incorporation and tax IDs for our new startup, as well as legal and financial documents attesting to the funding that we had raised from investors. To my relief, our interviewer didn’t seem to think any of this was a problem. She leafed through it briefly, and told us that it would take a couple days longer to process the new paperwork I had just submitted – but she was still going to approve us!

My wife and I walked out of the interview feeling elated. After all that preparation and anxiety beforehand, everything had gone so smoothly. After 17 years on various temporary visas, I was now finally about to get my green card. We called both our parents, shared the good news, and had a celebratory dinner that night. A small part of me even reminisced fondly on the past 2 decades. Being a transient had really lit a fire under my butt, kept me hungry, and kept me focused. “Maybe it was actually a good thing and helped me? I’m going to miss those days.”

Disaster

“Maybe it was actually a good thing and helped me? I’m going to miss those days.” Careful what you wish for. It just might come true. And it certainly did in my case.

The days went by and we were checking the online case-status every morning and evening to receive official confirmation of our approval. But nothing changed. A whole week went by, and we started to get worried. Two weeks went by, and that’s when we knew something was wrong. Shortly after, we got a letter in the mail. Our case was not approved. They needed us to submit more evidence.

According to the letter, they had looked up our new company on a government database, and didn’t find sufficient activity on it. They wanted us to provide evidence demonstrating that we were a legitimate and actively operating business. And even more worrying was the evidence they were asking for: annual reports, federal tax returns, letters from local governments and trade associations, company advertisements, payment receipts, W-2s, quarterly wage reports, detailed reports of goods and services being traded.

As we had mentioned in our paperwork, this was a completely new company, and a tech startup to boot. At the time of our interview, my co-founder and I were still working at our previous jobs. At the time when we received this request for additional evidence, our company was only 2 weeks old. We had already provided our legal incorporation documents, as well as proof of significant funding from professional investors. But as a tech startup that was merely 2 weeks old, we didn’t yet have a product to sell or advertise, we didn’t have prior tax returns, and our “payroll” consisted of just me and my co-founder. Over the next half year, we went on to file taxes and hire 5 more engineers and designers – all American citizens or permanent residents. But that was all in the future . In the present, we had very few of the documents that we were being asked to provide.

When I had talked to lawyers previously, I was reassured that I had little to worry about because our startup has been legally incorporated, and has secured significant funding from professional investors. But as I read the checklist of documents that we were asked to provide, the process didn’t seem conducive to newly created startups at all.

Regardless, I tried to do the best I could with the situation. I scrambled together as many of the documents as possible from their checklist. In addition, my co-founder and our investors also wrote letters of support, attesting to our company’s legitimacy, and explaining that it takes time for any new startup to fully recruit its workforce and start building and selling its product.

The immigration letter strongly suggested responding as soon as possible, within 1-2 weeks. And that’s exactly what I did. Over the next week, I eagerly checked my mailbox and the online case status religiously. But received no update at all. A couple weeks went by, and still no update. The weeks turned into months, and still no update. And that’s when I slowly realized that our immigration journey was nowhere close to being done.

The timing on this was also very bad. Just a few days after our immigration interview, my wife and I moved from our 1-bedroom city apartment into a townhouse in the suburbs… in preparation for our baby whom we were expecting 6 months later. What should have been an exciting and celebratory time, was instead a fearful one.

Given the radio silence from immigration, and the fact that our startup was so young and non-established, were we going to receive a denial on our Permanent Residency petition? From the stories that my wife was reading online, a lengthy silence like ours was commonly a precursor to denial. Should we even bother unpacking our stuff and buying furniture for our new home, or should we keep everything packed so that we can move abroad if needed? And where would we even go? My wife is an Australian citizen and it would take almost a year for me to get permanent residency in Australia. Is there a different visa that I can use to live in Australia during this time? Would New Zealand’s immigration system be better for us as a family? If not, what would we do with our newborn baby in the interim? Can I really be away from my firstborn for an entire year? Besides, is it even safe for my wife to fly across the world while heavily pregnant? What would we do if we received the denial when my wife was 36 weeks pregnant? Surely it would be unreasonable to move at that time, and find a new gynecologist and hospital in another country at the last minute. But if we stayed in America, we would be out-of-status, which could cause us severe legal problems for the rest of our lives? Could it even prevent me from getting permanent residency in Australia and joining my wife there in future?

The questions were endless, and the predicaments we could find ourselves in, were extremely anxiety provoking. For 6 months, we were living each day like it could be our last in America. Half of our belongings were still sitting in boxes and our new home was still unfurnished, because we thought we might receive a rejection notice any day. We spent considerable time every week brainstorming and investigating contingency plans, for all possible scenarios. I tried and partially succeeded in keeping a stoic mindset, but it was especially hard on my wife who wasn’t used to such immigration uncertainty. Doubly so while pregnant.

Back when I was young, single, and working at established companies, I felt invincible. “Of course everything would work itself out. And so what if it doesn’t.” But now, things were different. I was working at a brand new startup with minimal external legitimacy. And I had a wife to take care of, a baby on the way, a home that I need to provide for them – all the while wondering if we’ll be deported from that home on any given day. For the first time, I realized how untenable life is as an immigrant on a transient status.

It certainly didn’t help either that my right to work was also in immediate jeopardy. September 2021 gave way to February 2022, and we still hadn’t received any updates at all. During this entire time, I was using the earlier mentioned EAD in order to work at my startup. However, my EAD card expires in December 2021. By law, you’re only allowed to renew your EAD 6 months before it expires, but it can take over a year for the renewal petition to be processed. As a saving grace, filing to renew your EAD will automatically extend it by another 6 months, despite the absence of any formal paperwork stating this (something that many other government officials have a hard time believing, even after we show them the relevant government websites). However, that could still leave a couple months gap in between the existing EAD expiring, and the renewal being approved.

Thankfully (as I later found out after an entire night of anxious googling) applicants are still allowed to stay in the country for as long as their I-485 is pending. So we didn’t have to worry about packing up and leaving the country. However, if we didn’t receive our EAD renewals in time, both my wife and I would need to stop working at our respective jobs. Something that is hardly in the best interests of the startup that I had founded.

Recognizing the problems associated with their lengthy processing time for a simple renewal, the immigration agency does allow applicants to request expedited processing for renewals. Both my wife and I did exactly this, claiming that we needed to provide for our family and household expenses. A week later, we both received notices saying that our requests were denied. Given how on edge we were about our I-485 petition being denied, this other denial certainly didn’t lift our spirits.

2022 – The Marathon Ends

One week after our request was denied, I was sitting on the train commuting to work when I received an email stating that “there was an update” on our I-485 case. I knew this was one of the highest stakes messages I’ll ever receive. If the update was a denial, our entire lives would be turned upside down. I told myself mentally to remain stoic. And that no matter what happens, I can and will find a way to handle things. I pulled up the USCIS website, and to my relief, was notified that “Your card is being produced”.

According to people online, this was a very good sign. A few hours later, after my wife talked to an online USCIS rep to confirm our new address, we were notified that we were approved. And a week after that, we held in our hands our official green cards.

It’s hard to put into words the immense relief that we felt, simply knowing that we would be allowed to stay together, and continue living in this country. After 18 years, my immigration journey was finally at an end. For the first time in my adult life, I no longer had a stopwatch counting down to the day when I would be forced to leave this country.

A New Life

Within a month of receiving our green cards, we celebrated a second monumental event – the birth of our son. Unlike us, our son has the good fortune of being born on American soil – thanks to which, he has automatically received his American citizenship. After the marathon that I had to endure to get to where I am, it is amusing to think that my baby boy, spending his entire day napping and drinking, has already lapped me. He will never in his life need to justify his right to live, work, and pursue happiness in this land of opportunity. A tremendous privilege that I’m simultaneously thankful for and envious of. And one that I suspect he’ll never appreciate the full depths of.

It’s still hard to believe sometimes that my wife and I, two people who will always identify ourselves as immigrants, now have a son who is a natural-born American citizen. I just hope he will always remember his roots, and that his American citizenship is only possible thanks to his immigrant forebears.

Related Links:

Incredible.

I’m glad you finally achieved, I could feel the anxiety in the last part of the history.

I’m Colombian and I live in Spain and for us is very simple to get a european passport, just 2 years of residence to become Spanish.

The US is giving an inhumane treat to the people on this matter.

Enjoy your new status.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m reading this as a Nigerian in the tech industry, where the practical step in your career is to angle for relocation abroad.

But after reading this, I find the idea of relocation a lot less attractive, and certainly not in the US.

Thanks for sharing your story, Raj. I’m gad it worked out for you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow!

What a long journey!

Congratulations!

Being an immigrant myself, I can understand the feeling of uncertainty lived with. Thankfully I didn’t have to go through what you you’ve gone through.

LikeLiked by 1 person